|

| "The Secret: Portrait of Margareta and Francis K. Fong, a View of Pittsburgh Skyline from Mount Washington," 2011, oil on canvas, 24" x 30" |

Introduction

The author Francis K. Fong finished a painting on March 3, 2011, which he christened "The Secret." The purpose of this article is to use this painting to analyze Fong's technique for oil painting in portraying beauty.

Self-taught (mostly influenced by Vincent van Gogh), Francis was not without knowledgeable teachers willing to share their experience with him. As a freshman at Princeton, he took lessens in oil painting from a young painter, presumably an artist of some promise. Unfortunately, he soon got confused with all the terpentine thinning procedures. He rebelled, insisting on painting straight from the tubes without diluting the oils by solvents. His career as an art student was cut short as a result.

During the holiday season of 1998-99, Margareta, his wife, bought him a series of painting lessens at the local art museum.

Again, his insubordination got in the way. During the second lesson, Fong not only refused to use paint thinners, he objected to the teacher's admonition to use brushes that are "too large." An even more serious disagreement was the use of colors. Francis believed that, in oil painting, one should avoid using commercially available blacks, like lamp black or ivory black. Such blacks look dead. He insisted that more alive blacks can be obtained by mixing Vandyke brown and ultramarine blue. A range of "alive hard blacks," from "bluish black" to "blackish brown" are thus obtainable. He also theorized that, for "soft blacks," one might try mixtures of Vandyke brown and cerrulean blue.

Fong's second attempt at being an art student was again cut short. The teacher was abhorred by the insolence on the part of Fong, who had not done a single painting in his life.

One lesson the author learned is, there are no fixed rules in original work. In the making of things of beauty, rules are there to be broken, creatively. Observers of his work readily recognize the influence of van Gogh in Fong's earlier studies, of landscape and portraiture. Fong painted "The Secret" in an attempt to understand his own development, as much as in art as his personal growth his career as a scientist. Instead of copying the 19th century master, he assimilates certain aspects of van Gogh in developing a style of painting to make beauty. To enable this development, he attempts to understand van Gogh's development as an artist as reflected by his paintings of the baby Marcelle Roulin (1888).

The Title - An Overview

"The Secret" is, to date, Fong's most challenging attempt at placing people and still life subjects admist a panoramic view of a large U.S. city, of rivers, bridges, skyscrapers and distant neighborhoods.

|

| View from Mount Washington |

Prior to its completion, earlier versions of the picture were variously called "The Trimont," or "The View from Mount Washington," or "A Golden Sunset Over Pittsburgh," or "A June Sundown over Mount Washington and Pittsburgh." The background of this painting is the skyline of Pittsburgh, shown from a slightly different angle from Mount Washington that typifies the "Trimont Panoramic View."

|

| Point State Park Foundtain |

One reason Fong settles on the title, "The Secret," is as follows explained. The work depicts a late June afternoon in Pittsburgh, the city of three reivers which join in confluence at the Point State Park fountain. The cityscape and the distant hills beyond are golden, lit by the setting sun. Frank and Margareta at an imagined cocktail party at Trimont, are surrounded by people engaged in polite conversation. Below, on Margareta's right, is the Point marked by its fountain and, on Fong's left, are the rooftops of upscale restaurants that line Grandview Avenue on Mount Washington. Behind them is the skyline of Pittsburgh bordered by the rivers, Allegheny from the north and Monongahela from the south. The Ohio River begins at the Point, flowing to the west. Margareta whispers under her breath a secret to Frank, who appears to be mildly surprised, or perhaps a little scandalized.

There is a second, more subtle, origin of the title. The painting memorializes an event in late June of 2006. At that time, Fong had then recently recovered from his many ailments and hospitalization of 2005-06, ready to embark on a mission that was not readily disclosable, not even to Margareta and the immediate circle of his family and friends.

A June Sunset Over Pittsburgh Skyline

Four of the five tallest buildings in Pittsburgh are shown in this painting. The tallest structure, which is seen towering above the rest of the skyscrapers, is the U.S. Steel Tower. Completed in 1940, it has 64 floors. It is the fourth-tallest building in Pennsylvania; 35th in the United States.

|

| Pittsburgh's skyline bathed in a late June sundown |

The second tallest biulding is the BNY Mellon Center with 54 floors. The tallest building constructed in the 1980's, it was originaly called the One Mellon Center.

The third tallest structure is the PPG Place with 40 floors. Constructed in 1984, a year after BNY Mellon Center, PPG Place is, to this writer, the most eye-catching sight of Pittsburgh's skyline. The complex, which rests on 5.5 total acres including a 1-acre plaza, has 231 total spires shared across its six buildings. The neo-gothic style of the complex, particularly that of Building One, the principal structure, was chosen to bridge the architectural gap among the many styles in Pittsburgh, from the old gothic Cathedral of Learning (Univervisty of Pittsburgh) to the international style of the Westinghouse Building.

The fourth tallest building is the Fifth Avenue Place. Although it has only 31 floors, its spire reaches 616 ft above ground, only 19 ft lower than the 635-ft tall PPG Place, 1 ft taller than the fifth tallest building, One Oxford Center, a 45-floor skyscraper that stands outside the painting to the right.

Starry Night : A View from Mount Washington

As a companion piece, Fong began a work entitled, "Starry Night Over Pittsburgh." This work is in progress, shown below - unsigned.

|

| Starry Night - View of Pittsburgh Skyline from Trimont, 2011, oil on canvas, 18" x 20" |

Of interest is a comparision of this picture with "The Secret." First, Oxford One Center, which is in the latter painting, stands prominently to the right of PNY Mellon Center. Except for Fifth Avenue Place, which is also known as the Highmark Place, three of the four taller buildings, the U.S. Steel Tower, PNY Mellon Center and the PPG Place, are readily recognizable by the lights that outline their respective forms. The pyramidal top of the Fifth Avenue Place is lit on its sides. It appears on the left in "Starry Night" as a single upright lighted rod. The illusion is a result of lining up one of the lit sides with the tall lit spire. The remainder of the pyramid below the spire is merged in the dark of night. Grandview Avenue, now solitary after the business hours, glows warm in orange and gold, as does Interstate 376, the Penn-Lincoln Parkway on the north shore of the Monongahela.

Bridges Near Downtown Pittsburgh

The bridge on Fong's left is the Fort Pitt Bridge, a steel, double decker bowstring arch bridge that spans the Monongahela River near its confluence with the Allegheny River in downtown Pittsburgh. It carries Interstate 376, which concurrently runs as Interstate 279, between the Fort Pitt Tunnel and Pittsburgh.

|

| Photo of Fort Pitt Bridge |

|

| Fort Pitt Bridge, a Detail of "The Secret" |

It lands on the north shore of the Monongahela in downtown Pittsburgh. The traffic shown is the busy eastward-bound Interstate 376, headed for Forbes Avenue, where the University of Pittsburgh and its many hospitals are located, and beyond to Oakland, home for Carnegie Mellon University.

To Margareta's right is the Point and the bridges spanning the Allegheny between downtown Pittsburgh and North Shore. They include the Fort Duquesne Bridge, the identical Sixth, Seventh and Ninth Street

|

| Photo of the Point and Bridges Spanning the Allegheny |

Bridges, and the Fort Wayne Railroad Bridge.

|

| The Point and Bridges Across the Allegheny |

The Fort Duquense Bridge is nearly a twin of the Fort Pitt Bridge on the opposite side of the Point. It is also known as "the bridge to nowhere" due to delays in construction which left the northern end of the span hanging in midair for many years. From Pittsburgh downtown across the Allegheny, at Exit 1c, it accesses via the Infantry Division Memorial Highway (Route 65) the Heinz Stadium, home of the Steelers. A short walking distance from Heinz is the Rivers Casino. Parking at Rivers is free; but on football weekends, patrons of the Casino are required to pay a $20 garage fee. They have to show proof of their gaming in order to get that $20 refunded.

The Rivers is a world class casino with pleasing interiors adorned by sparkling lounges. Unfortunately its slots are tight, reportedly the tightest in the country. The blackjack game is better than the casinos in Indiana: the dealer stops hitting at soft 17, and the casino offers the "surrender" bet. Rivers also offers attractive surroundings at its Grandview Buffet. The food selection is large, and the dining area is graced by a panoramic view: Mount Washington across the Ohio River and, to its left, a glimpse of the Fort Duquesne Bridge from downtown Pittsburgh across the Allegheny.

|

| Views from Rivers Casino: (A) Fort Duquesne Bridge and (B) The Trimont |

The Sixth, Seventh and Ninth Street Bridges are named after Pittsburgh's prominent citizens, Roberto Clemente, Andy Warhol and Rachel Carson, respectively. They are three identical self-anchored suspension bridges. The Fort Wayne Railroad Bridge runs between nearby Hope Street on the right descending bank of Allegheny River and near the Eleventh Street on the left descending bank of the Allegheny. It carries two tracks on upper deck; its lower deck is not used.

Transitions from Conditions of Light to Shadows

In order to paint the effects of the setting sun, two color schemes for the skyscrapers were devised to show transitions from the conditions of light at the upper floors of the skyscrapers to lower floors in the shade.

|

| Two color schemes for Pittsburgh's skyline at sundown |

The choice of the color scheme on the right, as the warm orange yellows of the sun abruptly turn to the chilly purple shadows, reflects the overall color scheme for the distant neighborhoods, where the green yellows of the hill tops descend into the darker tones of sap green.

Influences of Two Masters

Fong began doing portraits a little more than a decade ago. Shunned by his teachers, he learned from van Gogh and Vermeer. The Dutch masters' influences are readily discernible in his 2000 painting of a young "Margareta on Her Wedding Day."

|

| "Margareta on Her Wedding Day," 2000, Oil on Canvas, 20" x 18" |

Touches of Vermeer are seen in the yellow dress, the flower bouquet, the large jar on the table, the colored window complex behind the curtains, and Margareta's silken hair and fair skin. Van Gogh's influence is seen undisquised in the brush strokes of the drapes and a copy of his flower painting on the wall.

In time, Fong developed his own style. Compare, for example, the young girl of 2002 and the woman in "The Secret."

|

| Comparison : (A) 2000 portrait of Margareta and (B) Current Work |

The smoothness of the thin oil layer of the 2000 painting (you can see the grains in the canvas) is replaced in the 2011 double portrait by a free-flow of brush work, in a multiplicity of primary and secondary colors. In this current work, whatever the influence of van Gogh in Fong's design of the skies, it's hard to find anything in Margareta's portrait identifiable as having its origins in that source of influence.

Van Gogh's Creative Process of Uglification

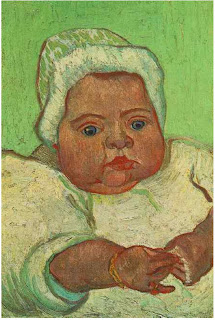

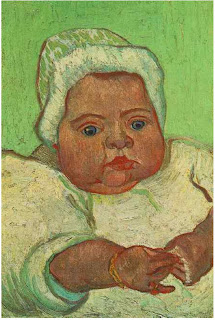

Among other things, Fong is unable to fathom Van Gogh's rationale when he, for example, painted Augustine Moulin holding her baby girl Marcelle, the version at the Metropolitan Museum in New York City. No baby can possibly be

that ugly!

|

| "Augustine Roulin with Baby," 1888, Oil on canvas, 25" x 20", Van Gogh |

Compare further Augustine Roulin's hands (by Van Gogh) with Margareta's in "The Secret."

|

Comparison : (A) Augustine's hands in "Augustine Roulin (La Berceuse)," 1889, oil on canvas,

36 1/2" x 28 5/8", (B) Margareta Fong's hands in this work |

It would seem reasonable to suggest that Fong does not compare unfavorably with Van Gogh, when it comes to painting human hands. But even while Margareta's hands, which hold a gin martini on the rocks with lemon twist, show long years of a pampered life, could it be that van Gogh painted Augustine's to look like animal claws in order to show Augustine's as a product of long years of toil and suffering, the likes of which are foreign to readers of this blog? We'll come back to this question after completing the discussion on Fong's making of "The Secret."

Interactions That Make "The Secret" Work

Two versions of Fong standing next to Margareta in "The Secret" were painted and compared. The one on the right (Design B) is preferred over that on the left (Design A).

|

| Two Designs, A and B, showing interactions between Frank and Margareta |

Design A is in want of interactions between Frank and Margareta. They stare in different directions, as if each were unaware of the other's existence. On the other hand, Design B suggests that something is going on between them. Margareta whispers something, like, "Don't look, but do you know ...?" His eyebrows raised in surprise, Frank keeps his line of sight away from Margareta as though she had not said something of intrigue that arouses his interest. There is material for gossip, for secret communication; hence "The Secret."

In making Design B, Fong found something wrong with his figure in A. His right arm appears uncomfortably short in comparison with his left. Also, the folds in his jacket are stiff and unnatural. Design B incorportes Fong's corrections.

Fleshing Out the Skull : Margareta

Fong also noticed a number of deficiencies on Margareta's face in A. The changes are shown in the comparison below.

|

| Changes made : from A to B |

The deficiencies in A are as follows: (1) Margareta looks as if she is "staring," (2) her hair appears to be a little coarse, (3) her right ear, in the shade, appears to be too sharply demarcated from her right cheek, and, (4) the protruding skull above the left cheek bone appears to be too pronounced. All of these defects would seem to be minor; Vincent would be unlikely to care about any further renovations. However, they contribute to an overall appearance of something amiss. Fong calls the process of retouching the portrait "fleshing out the skull."

The renovations are made as follows: (1) The "staring" was corrected by darkening the upper 1/4 of the irises under the darkened upper eyelids; (2) the hair is retouched using different shades of blonde - varying mixtures of cadmium red, lemon yellow and titanium white - from reddish to lemon yellow to white - with the darks in the hair made up of varying mixtures of dioxazine purple and lemon yellow; (3) shading the right ear with full-strength flesh tint; and (4) defining an outline for the bone structure around and below the left eyebrow area with a line in full-strength cerrulean blue.

Further fleshing out Margareta's skull, Fong restructured her eyes by adding details to redefine the arches of her upper and lower eyelids, thereby delineating the (pink) fleshy parts that go with the outer and inner lids.

|

| Eyes and nose jobs on fleshing out Margareta's skull |

Finally, to provide definition to the contours of Margareta's nose, Fong adds, below the yellow point at the peak of her nose, a faint light line in white to join the summit to the base of her nosal septum.

Fleshing out the Skull : Frank

|

| The skull effect on portrait subjects |

Margareta's skull, marked by her cheek bones, plays a part in capturing her likeness. The skull under Frank's facial features takes on an even more prominent role in his self-portrait. His cheek bones, the areas around his eyebrows and eye sockets form two semicircles, extending upward in confluence at the forehead. Fong's skull provides the underpinnings of his expressions. The skull is the immoveable foundation for modeling his inner feelings, of joy, of fear, or surprise.

|

| (A) Reference portrait; (B) with mouth puckered; (C) with raised eyebrows |

With (A) as the reference point, puckering Frank's mouth produces an expression of irritation (B). Beginning with (A), raising the eyebrows gives him a look of surprise. Expression (C), of course, is adopted for "The Secret."

Still Life

The flowers at the lower right corner consist of commonplace red and yellow lilies, some in bloom, others in buds, highlighted by an assortment of white and purple-violet dots of unknown species put together by the local florist. On consulting Margareta, Fong added two Indiana wildflowers, the Golden Alexander (Zizia aurea) and Culver's Root (Veronicastrum virginicum).

|

| Indiana wildflowers arising above a commonplace bouquet |

The additions not only remind him of the Indiana roots of the expanding Fong clan in this country, they serve to break up the unremarkable monotony of the rooftops.

Distant Allegheny Shores

The important Pittsburgh bridge, the Veterans Bridge, which carries Interstate 575 Crosstown Boulevard, disappears from the painting beyond the distant shores of the Allegheny shown.

|

| Distant Allegheny Shores, a detail |

The Veterans Bridge continues on north to the interstate highways that span the East and West Coasts of the United States.

Skies as Canvas for Abstraction

Fong loves to use the skies as a canvas for painting abstract designs. Here, the setting sun illuminates the left-slanted clouds in yellow, white and gold. The pattern is punctuated by the right-leaning corsscanvas caligraphic stroke in orange and red.

|

| Right-leaning crosscanvas caligraphic stroke punctuates pattern of left-slanted clouds |

|

| Abstraction in gold |

Above is shown the beginning and ending of the crosscanvas caligraphy in gold, orange, white and yellow.

Van Gogh's Baby Marcelle and Unraveling of "The Secret"

In 1888, Van Gogh painted baby Marcelle Roulin, potentially the ugliest baby in a known work of art. Conventional rules of beauty applied to humans have remained unchanged throughout history.

|

| Rules of conventional beauty : The Metropolitan Baby Ruolin (1888) vs. Baby Fong (December 2010) |

Van Gogh advanced his art of painting by learning how to draw. Painting the likeness of his sitter was no doubt as easy a task for Vincent as for the author. Van Gogh's 1888 painting of his mother's likeness is proof.

|

| Van Gogh's capture of his mother's likeness |

Therefore, one might suppose that van Gogh on purpose distorted the looks of the Roulin baby to make her ugly. Unfortunately, Fong is unable to unravel the secret of ugliness making in a creative process.

Not a single question has been raised as to why the baby girl Marcelle looks like an escapee from hell. Instead, the "furrowed brow and jowled cheeks of the baby Marcelle" are

praised as "carry[ing] an aspect of van Gogh's mature figures, roughly marked by life."

Fong rejects this praise. No aspect of van Gogh's mature figures measures up to the ugliness of the Metropolitan Marcelle. Among the most tortured look of the post-impressionism artist's "mature figure" is his 1889 self portrait with his cut right ear. Like Vincent's portrait of his mother, the detailed portrayal of the subject showed that it took the artist considerable time in laying out the subject's features. The pained, vacant stare is dignified, not ugly. Moreover, it is a reasonable likeness of van Gogh in a rare photograph by Victor Morin.

|

| 1986 Photo of van Gogh by Victor Morin |

|

van Gogh's dignified look of pain and suffering

|

Babies are difficult to paint. The techniques for painting adult faces are not readily applicable. The Metropolitan Marcelle is ugly, presumably because van Gogh did not know how to paint the infant girl. The proof is that he tried a second time, in late 1888 or early 1889, the same Augustine Roulin holding her baby Marcelle. This second painting is at the Philadelphia Meseum of Art. It is obvious that months after van Gogh painted the Metropolitan Marcelle, he still did not know how to paint the baby's features. He simply blurred them out rather than making Marcelle ugly again. The Philadelphia Augustine and Marcelle clearly shows that van Gogh took more time to complete the painting than he did the earlier, ugly Metropolitan picture.

|

| "Portrait of Madame Roulin and Baby Marcelle," 1888-89, oil on canvas, 36 38" x 28 15/16" |

Still in a third try, van Gogh in December of 1888 managed to do better, in a solo portrait of Marcelle Roulin. Unfortunately, van Gogh had not yet mastered the techniques suitable for capturing Marcelle's baby features.

|

| van Gogh's third attempt at painting baby Marcelle |

Vincent's failure to capture the likeness of a baby, in light of Fong's analysis of his technique for "fleshing out the skull," can be stated in two short sentences: (1) Babies and young children have faces that are padded by baby fat. (2) The spatial relationships of the features of their skulls are, as a result, not quite as discernable as those of adults. Therefore, it would seem reasonable to suppose that, the experts, who see a higher purpose in van Gogh's failing to capture baby Marcelle's likeness in the Metropolitan painting, are not painters themselves.

Gustov Klimt's 1907 Portrait of Adele Bloch-Bauer is a thing of great beauty. It took three years of fulltime work. Even its time-consuming move to the Austrian Museum on New York City's Museum Mile made

history in motion.

|

| Klimt's masterpiece on display in New York City |

By contrast, van Gogh in his letters to his brother, Theo van Gogh, at times spoke of his finishing a portrait "in one sitting." Often his rapid motion in painting produced works of striking originality. But to make portraits of quality, like his mother's portrait and his self portrait with a cut ear, it takes time and detailed planning. To test this theory, Fong attempted a number of quick versions of "The Secret." They were ugly and unworthy of him as an artist.

|

| One of several ugly versions of "The Secret" |

If Beethoven could have composed the Battle Symphony (Wellington's Victory, Op.91), a work of questionable quality, why couldn't van Gogh have painted a bad portrait? Why are the experts blind to this possibility?

Time will tell if correct answers to these questions provide a common ground for unraveling the author's mission in painting "The Secret."